Keeping Our Waters Clear

Keeping our Waters Clear

What We Stand to Lose When Invasive Plants Take Over

By Katie DeGoosh-DiMarzio, Environmental Scientist III, RIDEM Office of Water Resources

RIDEM Seasonal Field Technician, Peter Gnocchi, lifts a rosette of invasive water chestnut (Trapa natans) from Central Pond in East Providence (June 2016).

On a clear summer day in June, RIDEM Seasonal Field Technician Peter Gnocci cautiously leans over in the side of a canoe in Central Pond. He isn’t fishing, but instead grabbing a handful of an aquatic invasive plant called water chestnut (Trapa natans). First found just scattered here and there among the native lilies in the East Providence pond in 2009, this notorious invasive plant has grown to cover roughly 66-acres of the water, in this 137-acre reservoir.

That’s about 50 football fields of water chestnut coverage after just 14 summers. I think about the native lilac bush I planted in my yard ten years ago, and today it’s still just a shrub in my backyard, it hasn’t taken over the property. But water chestnut is sneaky and comes with a competitive advantage. It multiplies exponentially, starting off slow, and within a few short years it begins appearing in record amounts. The water chestnut population nestled in the Ten Mile Watershed is now the largest water chestnut population in the state of Rhode Island. It continues to spread downstream into Turner Reservoir (south of Newman Ave) and Omega Pond. Its distinct, thorny seeds have even washed up on shore at India Point Park after they drifted over the dam and down into the Seekonk and Providence Rivers.

The Ten Mile River Watershed Council have been longtime stewards of the Ten Mile River, working to improve recreational opportunities and extolling the importance of keeping the water and habitat healthy. For many years, dedicated watershed volunteers worked with RIDEM and the Rhode Island Saltwater Anglers Association on the river to carefully carry migrant river herring by hand and bucket over the dams that separated them from their historic spawning grounds upstream. However, by April of 2015, with the work of multiple partners, fish ladders had been installed at three dams to improve fish passage. Removing such obstacles for the fish reconnected over 340 acres of freshwater habitat that anadromous fish had been excluded from. The successful 16-year, $7.7 Million fish passage projects were the largest fish run restoration project in Rhode Island, and now volunteers simply need to tally the fish they see returning to the watershed from the sea. By 2020, over 20,000 fish per year were counted successfully making the trip upstream from the bay to the fresh waters of Turner Reservoir. River herring are an important keystone species in the Narragansett Bay ecosystem, serving as the base of a very large food chain. They play a pivotal role as food source for larger fish such as striped bass and bluefish, predatory birds such as bald eagles, herons, gulls and osprey, or wildlife like otters and eager snapping turtles. Pictures of such charismatic animals are often the featured subject matter of nature photographers that take to the waters of Central Pond, who later post their snapshots on social media to the delight of the Ten Mile Watershed Group.

In May, the shining waters are a calming oasis away from bustling urban sprawl, well buffered by lush, green conservation woodlands along the shoreline. The open water is a destination among paddlers who bring canoes and kayaks for an afternoon trip. The bridges on Newman Ave that bisect the reservoir are popular with local anglers casting off in pursuit of their next big catch, and statewide, the warmwater habitat is known as an important bass fishery. There is a winding greenway and trails along the shoreline, great for bikers, runners, and walkers to peek through the trees for a scenic view of the water.

But by August, the invasive water chestnut has emerged at the surface and grown to cover half of the reservoir under a gnarly mat of vegetation floating at the surface. Pictures posted of the pond look more like pictures of an open field as the water is no longer visible, now buried in shiny green leaves. Naïve paddlers who attempt to cut through the thick mass of leaves and stems quickly find their momentum blocked and as they struggle in the clogged waterway. Fishermen don’t even bother. One can only imagine what it’s like for the fish underwater. Where native lilies emerge in May and a few stems develop one leaf that only grows 4-8 inches across, one water chestnut plant tosses out up to 15 stems with a rosette of leaves that can each cover 4 square feet, shading 60 square feet of the water below. For a fish, it must be like someone closed the curtains and dimmed the sunlight. Predatory fish must swim farther to hunt down their meals in the darkness under the shade of chestnut leaves. The birds of prey soaring above the water in search of their next victim are flying blind. For smaller forage fish, their habitat structure has been physically altered with the addition of all these new fast-growing stems—as if someone dropped a forest into its living room, redirecting its patterns of movement. This rearrangement of things changes their foraging behavior, similar to people who wonder aimlessly around their favorite grocery store after corporate decides to switch the layout. Shopping trips take longer and patrons are not always successful at finding the item they were looking for. It’s the same for all the fish and wildlife that call Central Pond home, and these changes can affect an animal’s survival. Invasive water chestnut has not only ruined recreational pursuits, it also threatens a healthy balance of native flora and fauna, (central to a thriving ecosystem.) and is extremely difficult to get under control.

These things all add up to have economic consequences, when anglers aren’t stopping in for bait at their bait shop, local businesses serving the pond visitors lose income when they decide to travel to another lake, shoreline homeowners see a demonstrated drop in their property values which in turn leads to reduced tax revenues, and then the costs of restoration can be extremely high.

There is Hope

Luckily, the odds of controlling an invasive plant increase significantly if a newly established plant can be found early and weeded out before it begins taking over. RIDEM has had great success keeping water chestnut in check when found early, before plants claim an acre of surface water. Olney and Barney Pond in Lincoln, RI are great examples. While out on the water doing a survey, RIDEM staff found a handful of water chestnut plants in Barney Pond in 2019, so they decided to check upstream at Olney Pond in Lincoln Woods State Park. Sure enough, both ponds had the invasive plant, but in very small amounts. Plants from Barney Pond were enough to fit inside two laundry baskets.

There were slightly more water chestnut plants in Olney Pond. However, a strike team of 5 or 6 summer interns ventured out in canoes and kayaks to take out the water chestnut rosettes one mid-July day. The plants removed from a small 20 x 20 ft. area of Olney Pond all fit into the back of a one-ton dump truck on shore. Since then, RIDEM only spends about 2 days each summer removing plants from those locations. Every year, there are less and less plants to find, and by 2022 there were only a dozen floating rosettes to remove. Water chestnut is one of the few invasive plants that is an annual plant, germinating in early May, growing flowers, and starting to produce seeds in July, releasing those seeds in August, and then dying off in the Fall, all in the same year. It does not survive the winter, nor does it have an extensive root system. So, the trick to eradicating water chestnut is to get to the plants in June or early July and remove them from the water before they produce seeds. Removing the plant prevents it from multiplying next year, so every plant pulled this summer prevents more hard work next year. Unfortunately, those hardy, pointy seeds can hang out in the sediment for up to 12 years before they decide to germinate. So, for example, back in 2018 before the plants were discovered in Olney and Barney Ponds, the water chestnut plants were growing and giving off seeds that could be viable until 2030. Therefore, RIDEM will need to monitor those ponds for water chestnut each year, and pull whatever plants are found, but it is much easier to stay on top of the problem and manage it before it gets out of control. Similar monitoring and pulling efforts are underway in Belleville Pond in South Kingstown, Reynolds Pond in West Greenwich, Sylvestre Pond in Woonsocket, as well as Omega Pond in East Providence. Larger efforts are needed in the Blackstone River and Carl’s Pond with the Friends of the Blackstone/Watershed Council as well as at Turner Reservoir with the Ten Mile River Watershed Council. More water chestnut there necessitates recruiting some help from community volunteers for a muddy morning of water chestnut pulling.

Stay tuned for new announcements of any events planned for June and July, it makes for a very rewarding paddle. But even more important is to learn what water chestnut looks like! Being able to spot it early is our best chance at keeping it under control. Find resources online, and if you see a floating rosette while out on the water, take a picture and report it to RIDEM Office of Water Resources.

Aerial view of Central Pond, north of Turner Reservoir in East Providence. The water is covered with invasive water chestnut (Trapa natans) making fishing and paddling impossible (August 2022). Scan the QR code above to learn how to ID the plant.

Watch out for the worst weeds!

Learn to recognize the top two nastiest aquatic invasive weeds in Rhode Island and report plants to RIDEM.

Email pictures of the plant to [email protected] to report a new siting.

Invasive Water Chestnut

Look at the Leaves:

- float like water lilies

- triangle shaped

- toothed edges (not smooth)

- shiny, waxy finish

- Leaves are arranged in a circular rosette and radiate from the central stem

- Additional feather like leaves are underwater on the stem

Flowers in July

- Tiny, size of a pencil eraser

- Colored white

- 4 petals

- Found in the center of the rosettes

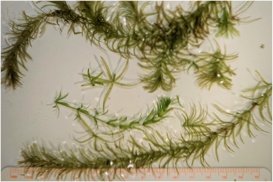

Invasive Hydrilla

Look at the Leaves:

- Leaves are submersed under water

- Blade shaped leaves

- Jagged, toothed edges (not smooth)

- Five leaves will attach to the stem together at one place (a whorl of 5)

- Each whorl may be centimeters apart along the stem in brand new growth, but they become more densely packed together one on top of each other, especially at the tip top of the stem

Fishing Activities Requiring a Permit

1.18 Permits are required for organized fishing tournaments for state fishing and boating access areas and for the following private access areas: Johnson’s Pond (Flat River Reservoir) in Coventry, and Waterman Reservoir, Glocester. Permits are required for six (6) or more persons and/or three (3) or more boats. Applications for the issuance of a permit must be submitted to the Division a minimum of three (3) weeks prior to the tournament. An organization may cancel a permitted fishing activity without penalty as long as written notice of cancellation is received at least three (3) weeks prior to the event. Failure to provide timely written notice shall result in a one (1) year revocation of an organization’s eligibility to receive a permit for any organized fishing activity. Exceptions for unforeseen occurrences (e.g. weather, natural disaster) will apply at the discretion of the Division. The decision of revocation shall rest entirely with the Division. Permit applications may be obtained by contacting RIDEM Division of Fish and Wildlife, 277 Great Neck Road, West Kingston, RI 02892, Tel: (401) 789-7481. Applicants must complete all required information. The Division reserves the right to limit the number of activities per location, per day, time period, or deny a permit for reasons of overuse or conflict with other activities.

a. The applicant must indicate on the application whether the fishing activity is a ‘closed’ or an ‘open’ activity. A closed fishing activity is an event having a fixed or restricted number of participants. An open fishing activity is an event having an unrestricted number of participants.

1. If the tournament is closed, the number of boats, vehicles, and participants must be entered on the application. The permit must be retained on site by the sponsor along with the list of participants and boat registration numbers.

2. If the tournament is open, the names of all participants and registration numbers of each boat on the day of the tournament must be made available to RIDEM Division of Law Enforcement. An estimated count of all participants, vehicles and boats shall be forwarded to the Division at least five (5) days prior to the start of the tournament.

3. Regardless if a fishing tournament is ‘closed’ or ‘open’, the organization must provide a report to the Division within five (5) days of the termination of the tournament which includes: the number of hours fished, the number of boats, numbers of participants, and, as applicable, the total number of largemouth bass and smallmouth bass caught as well as the total weight of all largemouth bass and all smallmouth bass processed at weigh-in. This report may be sent as a letter to RIDEM Division of Fish and Wildlife or by completing the Bass Tournament Count Form. Failure to complete and submit the required information within five (5) days shall render the organization ineligible to conduct further organized fishing events for one year from the said event. Such revocation shall include any events for which a permit was previously issued.

b. Applicants requesting a permit for a municipal or private ramp shall be responsible to obtain additional permits for these areas, if necessary.

c. These regulations shall not be interpreted as superseding any special boat ramp or state management area regulations.

d. Permits along with lists of participants and boat registrations, if applicable, shall be available during the tournament for law enforcement purposes and must be clearly displayed in the windshield of the contact’s vehicle.

For more information, contact Gabriel Betty at

[email protected] or 401-789-0281